The Royal Gurkha Rifles Regiment motto:

‘कांथर हुनु भन्दा मर्नु राम्रो” — Kaatar Hunnu Bhanda Marnu Ramro“

“Better to die than to be a coward”

The Royal Gurkha Rifles (RGR) has ever been and remains the very vanguard of the Gurkha frontline combat dimension of the British Army’s Brigade of Gurkhas, and related history of Nepali/Gurkha interrelationship with the British Army, and, more importantly, unique role in both British military and UK national/political histories.

This by way of introduction to the RGR from the Winchester-based UK’s Gurkha Museum, whose educational resources across some key areas of information about the Nepali – Gurkha unique contribution to [through the British Army] the story of the UK’s military history of the past 200 years, and by extension many decisive elements of the broader related history (from defence/retained independence, to overseas influence [pre and post European colonial-imperialist eras]) of the UK:

‘The modern Brigade of Gurkhas is an integral part of the British Army in the 21st century, providing well-trained and fully manned units, deployable across the full spectrum of operations and environments. The Gurkhas remain a strategic source of manpower, able to expand rapidly as required, with an unsurpassed competition for recruiting.

Gurkhas can boast no wastage in initial training and full retention, which leads to an enviable accumulation of experience. All Gurkhas are trained as ‘Infantry first’, and thus all Gurkhas are Riflemen at heart even if they join one of the Corps units. …

The main body of the Gurkhas form two battalions in The Royal Gurkha Rifles. One battalion is in the UK as part of 16 Air Assault Brigade and they are the specialist Air Assault Task Force. The other battalion is based in Brunei in South-East Asia and is the UK’s Jungle Warfare specialist battalion. All Brigade of Gurkha units continue to be heavily involved and at the forefront of all UK military operations.’

Source: https://thegurkhamuseum.co.uk/gurkhastoday/

Royal Gurkha Rifles (RGR) background and history:

In terms of formal constitution, the Royal Gurkha Rifles (RGR) – most famous in Britain and Nepal and internationally for the regiment motto [above] backed by a related history of incredible courage in the most extreme battleground frontline contexts and related ferocity of soldiery and officers — has a much more recent provenance than for example the Queens Gurkha Signals (QGS) or the Band of the Brigade of Gurkhas: the RGR was formed in 1994 from four separate Gurkha regiments. These were the (the Sirmoor Rifles being the most famous):

- 2nd King Edward VII’s Own Gurkha Rifles (originally, The Sirmoor Rifles)

- 6th Queen Elizabeth’s Own Gurkha Rifles

- 7th Duke of Edinburgh’s Own Gurkha Rifles

- 10th Princess Mary’s Own Gurkha Rifles

The actual origins of the RGR reach back to the earliest period, in South Asia, of the post-Treaty of Sugauli (2016). The Gurkha Brigade Association website’s Royal Gurkha Rifles page has a valuable History section, whose details are cited below:

The Gurkhas were first recruited into the British East Indian Company in 1816 and they distinguished themselves during the Indian Mutiny of 1857. Over 200, 000 Gurkhas volunteered to serve with the British-Indian Army in the World Wars.

After the partition of India in 1947, four of the 10 Gurkha regiments (2nd King Edward VII’s Own Gurkha Rifles: The Sirmoor Rifles, 6th Queen Elizabeth’s Own Gurkha Rifles (* see Gallipoli below in WW I section), 7th Duke of Edinburgh’s Own Gurkha Rifles, 10th Princess Mary’s Own Gurkha Rifles) opted to transfer to the British Army and formed the main part of the what is now called the Brigade of Gurkhas. Following the Government’s Options for Change in 1994, the four regiments of Gurkha Rifles were amalgamated to form a single regiment, The Royal Gurkha Rifles.

The RGR consists of two Light Role Infantry Battalions (1 and 2 RGR). They alternate between Brunei and the UK every three years. The Brunei based battalion specialises in Jungle Warfare and the UK based battalion is part of 16 Air Assault Brigade.

Source: https://www.gurkhabde.com/the-royal-gurkha-rifles/

Origins:

The Gurkha Rifles in fact sprang to life in 1815, even before the end of the 1814 – 1816 Anglo – Nepali War, and on the basis of the spirit of equality and above all, mutual self-respect, as the following excerpt from a New York Times (1964) news article on the Gurkhas and the British so well provides regarding the dramatic origin and its portentous sequel concerning the recruitment of the first three Gurkha Rifles regiments:

A JUNIOR British officer, Lieut. Frederick Young, became the first successful recruiter of Gurkhas in quixotic circumstances which perhaps offer a clue to the enduring loyalty and affection between the Gurkhas and their British commanders. Deserted by his Indian column, red – coated Lieutenant Young, with drawn sword, was surrounded by derisive Gurkhas. His Indian irregulars had broken and run when 200 tribesmen descended upon them, brandishing their dreaded fcufcris[*kukris] and shouting their old war cry, “Ayo Gorkhali!” (“The Gurkhas are upon you!”).

The Gurkha leader asked Young why he also had not fled. “I have not come so far in order to run away,” he replied. “I am here to stay.” His bearing impressed the Gurkhas. “We could serve under men like you,” the leader told him. He sheathed his kurki. Young sheathed his sword.

They shook hands.

Young was treated with respect and released. On his return to his commander, General Ochterlony, he asked to be allowed to seek recruits among Gurkha war prisoners —who were also being treated with respect. His first bid was at historic Dehra Dun camp. It was a sensational success. As Young put it: “I went in as one man and came out as three thousand.” Ochterlony ordered additional levies. Before mid-1815, while the war was still scrambling to its equivocal conclusion in 1816, three Gurkha regiments had been enlisted under the British Raj: the 1st, 2d and 3d Gurkha Rifles.

By the time of the great Indian Rebellion against British rule (the British ‘Raj’) of 10th May 1857 to 1st November 1858, also known as in British colonial history as the ‘Sepoy Mutiny’ (in Indian history the ‘mutiny’ was known as the War for Independence). But – some forty years after the Treaty of Sugauli — the British Army relationship with Nepal’s fierce and martial focused peoples who comprised what are better known as the Gurkhas, was clearly by this stage complete. The Gurkha Rifles were and remain both vanguard and bulwark of the Gurkha presence within the British Army. Image above is of the exterior of the besieged Hindoo Rao’s residency – a target during the rebellion for Rao’s close association with the British invaders.

We are very pleased that the UKNFS through our Gurkha community (retired and serving from Dorset to Aldershot and Kent) shared their perspectives on their perceptions on the Gurkha presence in not only the British Army, but also that presence’s role at key points in British history. They also directed to a number of different high-quality academic researchers books and papers on the subject of the Nepali – Gurkha role and exceptional contributions in support to the British side in the Sepoy Mutiny.

Throughout the process of developing this particularly important component of the UK Nepali cultural & social heritage, we shared the drafting and development of content, which received strong and enthusiastic support as covering the key aspects of the Gurkha – UK special 200 years+ relationship.

One of the papers referred to above, was particularly recommended as it filled in important gaps on a key early phase in the history of the Gurkhas in British history. The paper – source: https://www.spotlightnepal.com/2015/04/09/gurkhas-in-the-indian-mutiny/ — ‘Gurkhas in the Indian Mutiny,’ by Dr Bipin Adhikari (senior constitutional expert and the founding dean of the Kathmandu University School of Law), provides analysis of the excellent book by Frederick P. Gibbon, The Disputed VC: A Tale of the Indian Mutiny (London: Blackie & Son) is particularly commended for its details from a Nepali, South Asian, objective perspective. At the very heart of the critically important and decisive – for the British, East India Company side – role of the Gurkhas (effectively, Kingdom of Nepal, non-British nationals) in the Sepoy Mutiny manifested through the Sirmoor Rifles, founded in 1815. Ultimately the Sirmoor Rifles were the core component of what eventually became the RGR.

We cite the following excerpts from Dr Bipin’s paper, below – key entries in regard to the significance and nature of the Gurkha role in this climactic foreign/British imperialist versus subjugated peoples war in the history of European colonial imperialism, are indicated in bold:

‘The role of the Gurkhas was incredibly important to the Company to suppress the war of independence. The beginning of the rebellion was much unexpected. It grew rapidly and spread out very fast. It was very hard for Company forces to tackle the rebellion in the beginning. A Nepalese soldier at the front has been quoted as saying: “This war will soon be over. Jung Bahadur is going to march down to Lucknow with his army….He is our prime minister and commander-in-chief in Nepal. He offered to bring an army down to help you English two months ago, and now the government has accepted his offer.” That indeed helped change some of the scenario.

The deployment of tiny Gurkhas, the “Irishmen of Asia”, created panic among the rebels. Ted Russell, an ensign of the 193rd Bengal Native Infantry, stationed at Aurungpore, and one of the principal actors in the book, makes clear that the Gurkhas were eager to come in contact with the mutinous hordes and fight them out. These hordes were even seen by him running with terrified eyes and panting breath at different places. They fought like anything, throwing down musket and bayonet, and drawing their razor-edged kukris and plunged into the thick of their opponents, hewing them down and scattering them on every side by the fury of their charge.

The book lists many instances of the fierce character of Gurkhas and their bravery. One such instance is the chasing down of dozen or so Wahabi fanatics by a single Gurkha “highlander” during a rebellion rally … The book also glorifies the heroics of Gurkha “picket” that withstood the siege of Delhi for nearly three months under severe threat through bombardment and advancement of rebel fighters.

Similarly, describing the attributes of the Gurkhas and the Nepali Kingdom, Ted Russell states, “these Gurkies ain’t natives but furriners in Injia same as us, livin’ in a furrin country called Nepal, up amongst the Himalayas, which you’ve never ’eard on, I dare say. And the Gurky king ain’t a subject of the queen, like the Injian rajahs and nawabs and nizams and such, but free and independent, like voters at an election. I’ve fought side by side with ’em, … and they’re as good pals on a battle-field as any chaps from Battersea.” This clearly demonstrates the amount of admiration and fondness Ted Russell had for the brave and valiant Gurkhas.

The book also reveals the great loyalty the Gurkha contingent demonstrated towards their British friends. In his book, the narrator discusses of incidents where the rebels tried to persuade the Gurkhas to side with them, luring them with monetary incentives while also appealing to their religious inclination. However, the determined Gurkhas refused to side with the rebels and marched on with the objective of suppressing the Mutiny. This, according to the author, bred hate amongst the rebels towards the Gurkhas. This is clearly demonstrated in the following quote from the book: “Those monkeys of Gurkhas are renegades to their faith!” declared the [rebellious] Brahman priests to those mutineers in Delhi who were of their persuasion.” They prefer to receive the Englishman’s pay rather than follow the dictates of their holy men. Let them be outcasts! Spare them not! When we have destroyed the white men, then shall we deal with them, if any have escaped by that time !”

Even though the Gurkhas were finally overbearing, they also suffered terrible casualties from the mutineers. However, even the wounded ones refused to leave their post. Such was their determination that when the British comrades offered to assist and relocate the injured soldiers to a relatively less threatened zone, where they could receive medical assistance, they flatly refused instead preferring to stay by the side of their battling comrades.

Moreover, there is much in the book that shows how Gurkhas interacted with the British enriching each other with love and forbearance. Both contingents, according to the author, related to the tales of war and glorification of each other’s love for their homeland. The author in his book states, in the course of their interaction that “…the Gurkhas began to speak of their own beloved country of Nepal, by the mighty snow-clad Himalayas, of its wonderful beauty, and of its unequalled sport and wealth of animal life; and the Englishmen tried to explain the extent of their empire and the wonders of London, and told of their mighty ships of war and great sea-borne commerce.” This provided an opportunity for two diverse cultures to bond, albeit under extreme circumstances of war.

In contrast to the Gurkhas of Sirmur Battalion, according to Ted, the Gurkhas coming from Nepal, paled in comparison. Referencing the standards maintained by brave and valiant Gurkhas such as Merban Sing and Goria Thapa in Sirmur Battalion, the author described the Nepalese counterparts as comparatively, ” taller in stature, less sturdy and considerably dirtier” lacking the “true military swagger and jolly recklessness.”

The Gurkhas then assisted the British in capturing Lucknow from the mutineers and this dealt a great blow to the aspirations of the rebels. Through subsequent fighting, that lasted for months, the British were successful in driving the sepoys away from the great city of Lucknow and further north into the Terai region bordering Nepal. The author professes the relevance of this feat through the following statement: “everyone understood that all danger to the British raj was over through this day’s work.” The British had successfully defeated the Great Sepoy Mutiny and the Gurkhas had played a significant part in the suppression.’

Regarding the East India Company and its activity in South Asia the following source provides valuable context information: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/The-East-India-Company/

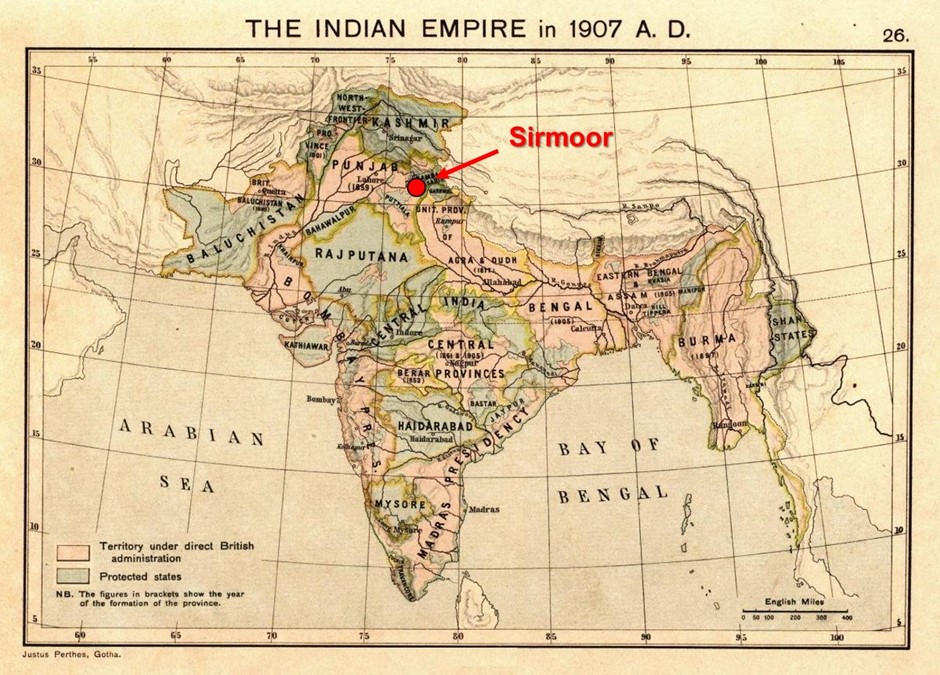

Regarding the Sirmoor Regiment, Sirmoor, and the Queens Truncheon:

Sirmoor (now in the north of the Republic of India) in British Army history is inextricably linked with the Sirmoor [Gurkha] Rifles Regiment’s key role in containing and then supressing the Sepoy Rebellion/Indian Mutiny, particularly in regard to the Siege of Delhi and the Relief of Lucknow in British occupied Hindustan. To date (2020) the story of Sirmoor, specifically through the Gurkha Sirmoor Rifles/Regiment has been little told – if one makes search online — in British Army history, and by extension early 19th Century UK British colonial history, and of course current [early 21st Century] British history in the era of a modern UK that is happily moving on from the shadows of its 19th and earlier 20th centuries racial supremacist ‘difficult’ past. Sirmoor, although a very small princedom within British India, was significant in the East India Company’s and subsequently British Government’s strategies for controlling the Indian sub-continent because:

‘… most of its Rajas were able rulers and fully supported the British Crown in the various conflicts and wars across India and even WW1 and WW2. They were well known for providing some of the best miners and sappers for aiding sieges.’

Source: http://www.dcstamps.com/sirmoor-princely-state-of-india-1815-1948/

Sirmoor in fact has a remarkable significance for Nepal and for Britain. A small princedom within the modern/post 1947 state of India, some hundreds of miles to the west of Nepal, the distance between Sirmoor and the current Western border of Nepal is approximately two thirds the distance – a reflection of the scale and success of pre-British East India Company military incursion, Nepal-Gurkha military prowess — as that between that of Nepal’s current western and eastern frontiers.

As such, given the Nepal (Gorkha/Gurkha) Sirmoor interconnections – aggressive (on a par with that of the British/’East India Company’ across the Indian Subcontinent) expansionist campaigns of the Nepal monarchy and state along the southern flanks of the Himalaya, the significance of Nepali-Gurkha military success and martial prowess can readily be understood.

For reference, the Sirmoor Regiment (that was founded in 1815, and developed in the decades following the Treaty of Sugauli, largely and finally becoming Nepali – Gurkha in terms of soldiery’ and officers) also interconnects with the earliest history of the Gurkha Engineers (eventually to become the Queen’s Gurkha Engineers), as the army of the princedom of Sirmoor although very small, had a reputation for very effective miners and sappers.

British Army recorded history in regard to the Gurkhas effectively begins with the Gurkhas of the Sirmoor Regiment, and that history focuses most of all on the so-called ‘Indian Mutiny’ (from Hindustani patriots perspective the ‘War for Independence’), particularly in regard to the role of the Gurkhas through the regiment in the Siege of Delhi and the Relief of Lucknow.

In effect, the Siege marked the holding in check of the ‘Mutiny’/Hindustani War for Independence against foreign/Western-European invasion and occupation, and the Relief, the turning of the tide against the ‘mutineers/Hindustani patriots’ (to give both occupier/invader and occupied/invaded perspectives) and the British ‘Raj’ regaining its seized dominions and consolidating these up to the collapse of the British Raj at the end of World War II. In the final stages of the ‘Mutiny’ the Sirmoor Rifles Regiment [Gurkhas] played a decisive role in support to British Army/East India Company military reconquest of central Hindustan/India.

As such, the British state and Crown owed the Gurkhas and ultimately the Kingdom of Nepal a major debt of gratitude for this politico-economic salvation of the Empire, which cannot be overstated for its strategic geo-political and economic value to the British Empire. This role played by the Gurkhas was further consolidated with the reconquest of the central Hindustan lands, through their significant military supportive interventions.

It cannot be doubted that the Nepali Gurkhas role in these decisive points in the suppression of the Sepoy Rebellion and the subsequent restoration of British rule in the sub-continent related not so much to numbers of Gurkhas involved, as instead, rather both equally their outstanding fighting skills from hand to hand (in practice riflery and prowess with the Kukri) to sapper work in conjunction with their reputation for ferocity combined with focus in fighting.

Here it is important to record that the Gurkha military impact was far out of proportion to actual Nepali-Gurkha military intervention numbers: the reputation for ferocity and military success that the Gurkhas had even by this time established, being a truly enormous strategic asset to the British state in this crucial struggle to maintain empire. To date (up to the start of the third decade of the 21st Century) the Gurkha role in British Empire and subsequent post-empire era history has been but rarely referred to, and when it has been it has tended to rank their [Nepali-Gurkha] role as of symbolic value, rather than the enormous strategic value it has had in decisive engagements in key campaigns of geo-politically crucial wars.

As such, and for these reasons the impact of the Gurkhas involvement was highly disproportionate compared to actual numbers in this critical point in British history. However across the second half of the 19th Century and into the 1900s this role was further consolidated as Gurkhas were deployed on the Afghan – North West Frontier territories and on the North East Frontier, with the former in particular being the most significant theatre of war for the British in the sub-continent, after the Indian Mutiny. The terrain in these two frontier locations was ideal for Gurkha/Gorkha deployment as essentially very similar to Nepal’s own topography, whilst in the case of the North Eastern Frontier (northern Assam) in part, some of the peoples (as with Sikkim and Bhutan) included those closely connected in terms of ethnicity with the Nepali Gurkhas themselves – indeed there is in the early 21st Century a swathe of districts within the Republic of India in these provinces that is known as ‘Gorkha land.’

Sirmoor Rifles related — The ‘Queen’s Truncheon’ and its history:

RGS and broader serving and retired Gurkhas have indicated the symbolic importance of the ‘Queens Truncheon’ in the history of the Brigade of Gurkhas role within the British Army, and commended the sources and information below regarding the Truncheon.

Replica of the Queen’s Truncheon — Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen%27s_Truncheon

The history of the Truncheon dates back to the time of the Indian Mutiny when The Sirmoor Battalion (later the 2nd KEO Gurkha Rifles) particularly distinguished itself by holding the Ridge during the siege of Delhi. Here they fought along side the 60th Rifles. During the prolonged action all its officers and 327 of its 490 other ranks became casualties.

For the Battalion’s outstanding service during the Mutiny, Queen Victoria was pleased to grant it a third colour inscribed ‘Delhi’ in English, Hindi and Persian. (The Sirmoor Battalion already held a Queen’s Colour and a black Regimental Colour.) At the same time additional distinctions were awarded to the Battalion. Henceforth, the rank and file were to be known as Riflemen, the title was changed to the Sirmoor Rifle Regiment and the Battalion was authorised to wear the uniform of the 60th Rifles (now The Rifles). The affiliation with The Rifles remains to this day.

It was not considered appropriate for Rifle Regiments to carry colours and uniquely Her Majesty Queen Victoria presented the regiment with the Truncheon to be carried in lieu of this third colour. The Queen’s Truncheon is ‘accorded all the dignities and compliments appropriate to a King’s Colour of Infantry’. Since the Queen’s Truncheon was passed to the Royal Gurkha Rifles it has continued to be held in the greatest reverence. Accordingly all New Recruits continue to be sworn in to the Regiment in the presence of the Queen’s Truncheon.

Source: https://www.gurkhabde.com/history-of-the-queens-truncheon/

BBC news article on the Queens Truncheon: The regiment which later became the 2nd King Edward VII’s Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles) was raised in northern India in 1815 as the Sirmoor Battalion, a local corps until 1861 when it became a regular regiment in the Bengal Army. During the Indian Mutiny it distinguished itself when, for more than three months, it held a key post on the ridge which was the main British position during the Siege of Delhi. During that Siege and the assault to capture the City it suffered 327 dead and wounded out of 490 all ranks, and formed a strong affiliation with the 60th Rifles,

Because Rifle Regiments did not carry Colours, the newly titled Sirmoor Rifle Regiment had to stop doing so, which meant that the privilege of carrying a third Colour was lost. To keep the distinction Her Majesty Queen Victoria authorised the replacement of the third Colour by a Truncheon.

The Truncheon, which is about 6 feet high and made of bronze and silver, is carried on parade by the Truncheon Jemadar, whose post was added to the Establishment for the purpose, escorted by two Sergeants and two Corporals. Like a Sovereign’s Colour it is greeted with a Royal salute when it appears. Comments are closed for this object.

Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/OlrZr5X5RZOwqKSMlJlapg

Videos relating to the Queen’s Truncheon:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S117K92iAac — The Queen’s Truncheon presented to Her Majesty The Queen. 568 views •Jul 16, 2019

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5JpRF-pVIg8 — Gurkhas swear oath on Queen’s Truncheon 12.12.11 18,102 views •Dec 13, 2011

The Gurkha Rifles and the two world wars:

World War I:

Some 200,000 Gurkhas (Nepalis) were involved in World War I, out of which some 16,000+ deaths resulted: with the 2nd King Edward’s Own Gurkha Rifles particularly constituted the core fighting force, with other regiments (Signals, Engineers, the Band of the Brigade of Gurkhas, particularly) contributing to the British effort in the war.

All not having the same geo-political strategic importance of the sub-continent interventions of the previous century, the ‘Great War’ as World War 1 was known, saw different outcomes for the Gurkhas, especially the riflemen.

On the one hand there were the horrific experiences of a poorly thought through by the War Office in Whitehall, deployment to the trenches of the Western Front, and the depressing experience of Gallipoli that resulted from essentially a sound strategy and good start being transformed into a bloodbath and eventual retreat because of largely poor communications and related tactical errors by the British Army. On the other hand, the heroism and the martial glamour of the Gurkha reputation for ferocity and success in appropriate combat situations, advanced considerably through certain battles and campaigns. Most famous of these were ‘Gurkha Bluff’ in Gallipoli (perhaps the best known success of the courageous British forces), the Fall of Bagdad, and participation in the legendary campaign of Arab uprising against the Ottoman Empire [the Turks] led by Captain (later Colonel) T.E. Lawrence – better known as ‘Lawrence of Arabia.’ Gurkha Bluff – Gallipoli perhaps more than any other engagement, gave Nepal’s Gurkhas a truly global renown for their deadly fierceness in battle. Such renown carries weight in the human heart (and certainly that of the military strategist who considers the possibility of coming up against, or deploying such a phenomenal fighting force) rather than dry numbers and places those numbers where deployed in.

The Fall of Bagdad, the fabled ancient city of Mesopotamia [later, capital of Iraq) is comparable to the Siege of Delhi and Relief of Lucknow at the time of the Indian Mutiny, for its strategic relevance as Bagdad had for centuries been the key city of the Ottoman Empire in its south-eastern territories in the Gulf – Middle East region: its taking by the British forces (the UK after WW I took effective control of the Iraq – Mesopotamia region as a British Protectorate under a League of Nations Mandate [France took the lands to the West, Syria, in a similar capacity]) marked the end of Ottoman hegemony in the broader region, and the birth of the new political borders map of the Middle East. Consequently, again, the Gurkha role at a decisive frontline engagement level had a broader global level significance for not only British overseas power, but in ushering in a new chapter in world history.

In regard to ‘Gurkha Bluff’ in the Gallipoli campaign, and the role of the Gurkhas through Laurence of Arabia’s British support on the British supported Arab uprising against the Ottoman Turks, which ushered in the eventual liberation of the Arab lands of the Middle East and the Arabian Peninsula and subsequent post WW II political geography of this part of the world, we provide excerpts from two sources below. These indicate both the practical level and types of the Nepali – Gurkha role, and also the latter’s geo-political strategic impacts.

On Gurkha Bluff, Gallipoli:

Image source: UK National Army Museum – Gurkha infantry in Gallipoli

We have had recommend to us this valuable very educational video regarding the Gurkhas in Gallipoli – also showing the full size of a WW1 Gurkha Rifles kukri: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tA2MAKkrHqg

Also recommended to us in the course of our engagement and research for the Gurkha component of the information resource is the interview below, as it gives a thorough overview of the Gurkha Rifles role at Gallipoli.

“I first met the 6th Gurkha Rifles in 1915 in Gallipoli. There I was so struck by their bearing in one of the most desperate battles in history that I resolved, should the opportunity come, to try to serve with them. Four years later it came, and I spent many of the happiest and, from a military point of view, the most valuable years of my life in the Regiment.”

Field Marshal Sir William Slim

“When everything comes out, this Dardanelles show will prove to have been the most mismanaged show on earth with thousands of lives that have been unnecessarily thrown away”

Lt Col Allanson, 6 GR

On April the 24th 1914 orders were received for the 1/6th Gurkha Rifles to embark at Port Said on s.s. Dunluce Castle for the Dardanelles (see Maps 1 and 2). The ship anchored off Sedd-al-Bahr at 1230 on April the 30th. The Battalion subsequently left Murdos for Alexandria on 21st December, and little did they know what was in store over the next 8 months in what became known as the Gallipoli campaign.

Overall the Gallipoli campaign was a disaster from beginning to end. The mission was ineptly commanded and poorly equipped. After nine months of deadlock and the loss of more than 100,000 lives the allies eventually withdrew their attack on the peninsula. The offensive’s ultimate aim was to push through the Dardanelles Straits and capture Constantinople, the Turkish capital. If a breakthrough had been achieved, the Turks, who were allied with the central powers (Austria and Germany), would have been unable to prevent Britain and France from joining the Russians in the war against Austria-Hungary and Turkey.

However, the 6th Gurkhas gained immortal fame at Gallipoli during the capture from the Turks of the feature later known as “Gurkha Bluff” and at “Sari Bair” they were the only troops in the whole campaign to reach and hold the crest line and look down on the Straits which was the ultimate objective.

Gurkha Bluff

The second despatch of General Sir Ian Hamilton, Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, dealt with the Krithia battles of May and June 1915.

“During the night of the 10th/11th May the 6th Gurkhas started off to seize this bluff. Their scouts descended to the sea, worked their way for some distance through the broken ground along the shore and crawled hands and knees up the precipitous face of the cliff. On reaching the top they were heavily fired on. As a surprise the enterprise had failed, but as a reconnaissance it proved very useful. On the following day Major-General H. V. Cox, commanding 29th Indian Infantry Brigade, submitted proposals for a concerted attack on this bluff (now called Gurkha Bluff). …

The following General Routine Order (16) was published on May 17th, 1915:

“In order to mark the good work done by the 1/6th Gurkha Rifles in capturing the Bluff on the coast west of Krithia. The General Officer commanding has ordered that this Bluff will in future be known as”Gurkha Bluff” (see Photograph 2).

The Krithia battles were most significant as they proved that the original British assumption of a swift victory over an indifferent enemy was grossly mistaken. Thereafter Helles would become the scene of numerous attrition battles and success would be measured by an advance of a hundred yards or the capture of a trench.

The total battle casualties sustained by the 1/6th in the Cape Helles battles were 96 killed and 383 wounded. Capt F. B. Abbot and Capt D. G. J. Ryan were awarded DSOs and Lt H. C. Poynder the MC.

Sari Bair

Extract from Sir Ian Hamilton’s despatch dated 15 December 1915:

“General Baldwin’s column had assembled in the Chailak Dere on 6th of August, and was moving up towards General Johnstone’s headquarters. Our plan contemplated the massing of this column immediately behind the trenches held by the New Zealand Infantry Brigade. Thence it was intended to launch the battalions in successive lines, keeping them as much as possible on the high ground. Infinite trouble had been taken to ensure that the narrow track should be kept clear, guides also were provided; but in spite of all precautions the darkness, the rough scrub-covered country, its sheer steepness, so delayed the column that they were unable to take full advantage of the configuration of the ground, and, inclining to the left, did not reach the line of the Farm – Chunuk Bair till 5.15 a.m.

But now, under that fine leader, Major C. G. L. Allanson (see Photograph 3), the 6th Gurkhas pressed up the slopes of Sari Bair (see Map 3), crowned the heights of the col between Chunuk Bair and Hill Q, viewed far beneath them the waters of the Hellespont, viewed the Asiatic shores along which motor transport was bringing supplies to the lighters.”

In Allanson’s own words “At the top we met the Turks; Le Marchand went down, a bayonet through the heart. I got one through the leg, and then, for about ten minutes, we fought hand to hand, we bit and fisted, and used rifles and pistols as clubs; blood was flying like spray from a hair wash bottle. And the Turks turned and fled, and I felt a very proud man; the key of the whole peninsula was ours, and our losses had not been so very great for such a result. Below I saw the Straits, motors and wheeled transport, on the roads leading to Achi Baba”

To continue with General Hamilton’s despatch:

“Not only did this battalion, as well as some of the 6th South Lancashire Regiment, reach the crest, but they began to attack down the far side of it, firing as they went at the fast retreating enemy. But the fortune of war was against us. At this supreme moment Baldwin’s column was still a long way from our trenches on the crest of Chunuk Bair, whence they should even now have been sweeping out towards Q along the whole ridge of the mountain. And instead of Baldwin’s support came suddenly a salvo of heavy shells. These falling so unexpectedly among the stormers threw them into terrible confusion. The Turkish commander saw his chance; instantly his troops were rallied and brought back in a counter-charge, and the South Lancashire’s and Gurkhas, who had seen the promised land and had seemed for a moment to have held victory in their grasp, were forced backwards over the crest and on to the lower slopes whence they had first started.”

Every British officer in the 1/6th had been killed or wounded, except for the Medical Officer Capt Phipson, and the withdrawal was carried out by Subedar-Major Gambirsing Pun, who spoke no English, and relied on Capt Phipson (see Photograph 4) to interpret for him. The Battalion withdrew in good order and Gambirsing was awarded the MC for his leadership and gallantry. Total casualties amounted to 204 all ranks in three days fighting, of whom 45 were killed, three of them British officers. Allanson and Phipson were awarded the DSO, and of the many Battle Honours awarded to 6GR “Sari Bair” must rank as outstanding. …

Post Script:

It was the considered opinion of the Lt Gen Sir Reginald Savory, who served at Gallipoli with the 14th KGO Sikhs that the 1/6th Gurkha Rifles were “the outstanding battalion of the Gallipoli Campaign”.

General Sir Ian Hamilton’s secretary, in a letter acknowledging a Christmas card from the Regiment, says “It is Sir Ian Hamilton’s most cherished conviction that if he had been given more Gurkhas at the Dardanelles he would never had been held up by the Turks”. He was probably right!

6GR were subsequently awarded the Battle Honours “Helles”, “Suvla”, “Krithia” and “Gallipoli 1915”.

Today a painting by Terence Cuneo showing Major Allanson and the 1/6th on the crest of Sari Bair is displayed by the Royal Gurkha Rifles, successors to 6 GR (see Picture 1).

Author: Colonel P D Pettigrew

Source (website of the 6th Gurkha Rifles): https://www.6thgurkhas.org/the-regiment/gallipoli-campaign/

The Arabian Peninsula and ‘Laurence of Arabia’ – the role of the 3rd Queen Alexandra’s Own Gurkha Rifles:

Gurkha soldiery and officers were a key part of Captain TE Laurence’s extraordinary and incredibly successful military campaign in Arabia, Palestine and beyond, British military campaigns to subvert and assist to become independent and under a new, British, hegemonic influence, these long established Ottoman Turkish Empire territories.

Gurkhas in Palestine, and map of Ottoman Empire c. 1915

In an attempt to foster Arab resistance to the Ottoman Empire (the large multi-ethnic empire which ruled much of the Middle East, including the Arabian Peninsula, during the First World War) The Allies began to provide Arab leaders with resources and sent intelligence officers into the region to coordinate and assist their efforts. Perhaps the most famous of these intelligence agents is Captain (later Colonel) Thomas Edward Lawrence, a British Army soldier and archaeologist, better known as Lawrence of Arabia. From 1916-1918 Lawrence led a combined British and Arab military force in raids against Ottoman positions and railways, tying up troops and disrupting the Ottoman war effort.

In October and November 1918, at the height of these hit-and-run campaigns, Gurkha soldiers from the second and third battalions of 3rd Queen Alexandra’s Own Gurkha Rifles were recruited into this group under the command of a Captain Scott-Higgins of 3/3GR. Though having little experience of camel-riding, just under 30 soldiers are believed to have volunteered for ‘Unt Ka Kam’ or ‘Camel Work’ and departed in total secrecy on August 13th 1918 for Suez. An account given by one Havildar Manhabadur Gurung relates how, after a mere week spent training how to ride camels, the volunteers were sent into the desert. The Gurkhas rode for over three weeks, almost without halt or fires, in order to avoid detection by Ottoman troops, to meet with a larger force made up of a variety of allied troops. This force then began raiding along the Hejaz railway, with the Gurkhas taking part in the breaking of the line in several places.

These raids (and others like them) aimed to prevent reinforcements being brought up to the Ottoman front lines quickly in the event of an Allied attack and are considered to have severely hampered the Ottoman ability to reinforce their troops to the North during the final stages of the war.

Source: https://thegurkhamuseum.co.uk/telawrence/

World War II:

The Brigade of Gurkhas was deployed in multiple theatres throughout the Second World War with all components of the Brigade playing crucial parts in Gurkha frontline action. The Gurkha Rifles were ever to the forefront of this action. In total an estimated quarter of a million Gurkhas served with the British Army in Europe in World War II.

In the West/European theatre of war, the Gurkhas first entered service in Cyprus (a key strategic British possession in the Eastern Mediterranean, halfway between southern Turkey and the north of Egypt), from there deployed to Egypt. As such they served with courage and to great effect in the two decisive battles of the North African theatre of war, at El Alamein; the first saw the British Army decisively check the until then relentless advance of the German Army under Field Marshal Rommel; the second Battle of El Alamein under General Montgomery was the start point of the British forces pushing the German Army out of North Africa. It cannot be doubted that the presence of the Gurkhas played through their battlefield ferocity and reputation, a significant supportive part in these two key battles for the control of North Africa, the Suez Canal, and Middle East.

Subsequently, the Gurkhas played their part in the British Army part of the Allies invasion of southern Italy: notable service including the battle for and taking of the almost impregnable Axis fortress of Monte Cassino (a converted/fortified mountain-top historically important Benedictine monastery). Multiple key engagements in which the Gurkhas, and especially the Gurkha Rifles made significant contributions in the Second World War included largely Italy (but also in the final stage of the war in Europe, Greece [1944 – 1945] too) are recorded in Battle Honours details at the end of this section.

Of equal importance to the West, were the Gurkha contributions to the British War effort in the Far East (Battle Honours for this this part of the war are also referred to below). In regard to the latter, the main theatres of war in which the Gurkhas were present and played honourable parts, essentially were Burma, and before the Burma campaigns, Malaya and Singapore.

Burma and the Gurkhas:

The Gurkhas in Burma (Myanmar) — source: https://www.chinditslongcloth1943.com/32-gurkha-roll-call.html

More on Gurkha ferocity and ingenuity in the four campaigns that took place from the time of the Japanese seizure of Burma to the Japanese Army expulsion from the then British colony – some stories and accounts:

The following stories were particularly recommended by the various Gurkha authorities (British Army serving and retired Gurkhas of multiple generations) supporting, contributing to and advising on the UKNFS facilitated UK Nepali cultural & social heritage project information project content.

‘ … My father was sent to India during WW 2 to take command of a Gurkha regiment that was slated to go to Burma. He had nothing but tremendous respect for the men he commanded and praised them every chance he got.

Three cases may highlight how they operate.

- Dad and a patrol were moving through the jungle on a narrow dirt path when, from up ahead a sound was heard, everyone went to ground and prepared to ambush whoever was coming down the path or to surprise them from their hiding place if they were friends. They turned out to be a Japanese patrol. After the firefight a few Japanese prisoners were held. Dad told the men to bury them and walked off to check on a few things and he then returned to the prisoners. The dead Japs were in the bottom of a hole that had been dug and the live prisoners were standing in the bottom. The Gurkhas were getting ready to shoot the prisoners. Dad asked the Jemadar (minor ranked officer in the Indian army – dad’s men came from the hill forts in India and were NOT Nepalis) what was happening and the response was that they were going to shoot them and then bury them because it would not be a nice thing to bury them alive. Dad, of course, expected them to bury the dead but take the live prisoners back for interrogations. THEY TAKE ORDERS LITERALLY!

- The second case was when one of Dad’s men went a little stir crazy while in barracks and would not exit the barrack he was in and would shoot at anyone who tried to get into the barrack. Dad had no idea what to do and a Gurkha Sergeant Major told dad that he would sort everything out. He went to the barrack door, called out to the man inside, opened the door, no shot was fired, a minute later the Sergeant exited the barrack room cleaning his Kukri, he resheathed it, and told my dad that the man would no longer shame the regiment. EVEN A GURKHA DOESN’T MESS WITH OTHER GURKHAS!

- Apparently while in Burma the Gurkhas, even though they were ordered to stay in the camp overnight, would sneak out looking for Japanese sentries. If they found one they would silently come up behind them and feel their boots to see if there were two toes (called Tabi in Japan) and slit their throats if they were wearing these Japanese style boots. Also, on the way back to camp they would sneak up on any guards set around their camp and silently undo their shoe laces and tie them together. My father told me about this as well and also told me that every night there would be swearing from the camp guards as they tried to move off and fell flat on their faces.

I’m guessing the Japanese were terrified of them!’

Source – Lance Chambers in Quora: https://www.quora.com/Are-British-Gurkhas-really-as-good-as-people-say-they-are

‘ … My Grandad fought in Burma during WW2 for the Royal Artillery and fought along side the Ghukhas. … Anyway in memory of him, he often talked about the Gurkhas and this is what I remember.

Whilst his battalion often moved in the valleys for the day, the Gurkhas would be high up on the difficult to navigate ridge, giving cover. Despite this, they would always have camp set-up when the RA got there!

They were truly amazing. if they hit a bottleneck of enemy, these guys would literally go in as a problem solving squad and deal with it. My Grandad always used to say that they were truly mystical back then and seemed to understand and melt into the jungle in some way.

One taught him how to defend himself with a knife, which in itself was amazing because he said they kept themselves to them themselves in camp. the kind of training a soldier in the UK army doesn’t get! It saved his life one day when he found himself isolated and being hunted by an enemy soldier.

He used to laugh that the Gurkhas could not expose the blade of their knife without it drawing blood during time of war and after they cleaned and sharpened them at the end of each day, they would have to nick their thumbs with it. I don’t know if that was true or not, but it just underlined every time he talked about them, his eyes lit up with the sheer amazement of them.

When I was older I asked him if he thought that the Gurkhas were better than the SAS. His answer was that in jungle warfare no-one was better and he went further in saying that he literally owed his life to those men that protected them in Burma.’

Source – Dave Kind in Quora: https://www.quora.com/Are-British-Gurkhas-really-as-good-as-people-say-they-are

There was Havildar Gaje Ghale, who in May 1943 rallied men while under heavy mortar fire and led them forward. Approaching a well-entrenched Japanese enemy, the platoon came under withering fire and Havildar was wounded in the arm, chest and leg by an enemy hand grenade.

Without pausing to attend to his serious injuries and ignoring intensive fire from both sides, he led his men forward to close encounters with the enemy.

A bitter hand-to-hand struggle ensued and Havildar dominated the fight with dauntless courage and superb leadership. He hurled hand grenades, covered in blood from his own wounds, and led assault after assault, encouraging his men by shouting the Gur- khas’ blood-curdling battle cry.

Spurred on by the will of their leader, the platoon stormed the hill and inflicted heavy casualties on the Japanese.

In Burma, during intensive fighting in June 1944, Rifleman Agam Singh Rai and his men fell under intense fire from a 37mm gun. Without hesitation he led his men towards the gun under heavy fire. Despite this, Rifleman Rai and his men quickly reformed for a final assault.

In the subsequent advance brutal machine gun fire and showers of grenades from an isolated bunker position caused further casualties.

Once more, Rifleman Rai pushed ahead alone with a grenade in one hand and his Thompson sub-machine gun in the other. He wiped out all four occupants of the bunker.

Source: https://www.express.co.uk/expressyourself/98467/Our-greatest-Gurkha-heroes

First and Second world wars Gurkha Rifles Battle Honours (source: Wikipedia):

The regiment was awarded the following battle honours:

• Bhurtpore, Aliwal, Sobraon, Delhi 1857, Kabul 1879, Kandahar 1880, Afghanistan 1878–80, Chin-Lushai Expedition 1889-90, Tirah, Punjab Frontier

• First World War: La Bassée 1914, Festubert 1914 ’15, Givenchy 1914, Neuve Chapelle, Aubers, Loos, France and Flanders 1914–15, Egypt 1915, Tigris 1916, Kut al Amara 1917, Baghdad, Mesopotamia 1916–18, Persia 1918, Baluchistan 1918

• Interwar Years: Afghanistan 1919

• The Second World War (main theatres of involvement: North Africa, Greece, Burma: El Alamein, Mareth, Akarit, Djebel el Meida, Enfidaville, Tunis, North Africa 1942–43, Cassino I, Monastery Hill, Pian di Maggio, Gothic Line, Coriano, Poggio San Giovanni, Monte Reggiano, Italy 1944–45, Greece 1944–45, North Malaya, Jitra, Central Malaya, Kampar, Slim River, Johore, Singapore Island, Malaya 1941–42, North Arakan, Irrawaddy, Magwe, Sittang 1945, Point 1433, Arakan Beaches, Myebon, Tanbingon, Tamandu, Chindits 1943, Burma 1943–45.[3][12]

From the period of the end of the Second World War (WWII) and commencement of Indian Independence, to the creation of the Royal Gurkha Rifles (RGR) in 1994, and including the Falklands War:

This period saw the Gurkha Rifles battalions serving in a number of theatres of war, from conventional warfare to anti-guerrilla operations and counter insurgency, as well as training and policing type support. Malaya (the tour of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles lasted there from 1948 to 1960), Borneo (Sabah, Malaysia), Brunei, were particularly active areas of service in this period, whilst Borneo and Brunei remain important to this day for training purposes. In addition, in the case of Borneo (North Borneo / Sabah Province of Malaysia) the Gurkhas are renowned for their feats of agility and endurance on mountain climbing and marathon, hill racing circuits at Mt Kinabalu (continuing to this day). In 1974 the Gurkha Rifles (10th PMO Gurkha Rifles) also saw deployment to Cyprus in defence of the UK sovereign base areas (SBAs), to support pre-existing British Army presence in these territories, after the Turkish invasion of the northern parts of the East Mediterranean island.

In 1992 the 1st and 2nd Battalions merged whilst the Gurkha Rifles final years of being based overseas in Hong Kong drew to a close, with their leaving for the UK in 1994 (a regimental depot had been established in Hampshire long before this) which was the year that four original Gurkha rifles regiments combined, and the Royal Gurkha Rifles was finally born. For related reference, the Gurkha Rifles along with both the Gurkha Signals (later QGS) and the then Gurkha Transport Regiment were all originally based in Singapore, making Hong Kong their new home from 1971.

Singapore: the Gurkhas from the early days of its history, the Gurkhas have had a special relationship with the island state of Singapore (a former British colony on the Strait of Malacca, and strategically vital entrepot on the route between the Suez Canal and the Far East), where many still serve within the police force: an interesting anomaly from British colonial history.

The Falklands War:

Clearly out of the 1945 to 1994 period, the Falkland War (2 April 2nd 1982 to the 14th June 1982) stands out by far as the most important campaign the Gurkhas (1st Battalion 7th DEO Gurkha Rifles)participated in: important because of the conflict’s geo-political importance for the United Kingdom, perhaps in such terms – although not anywhere near the same scale – as important as the Indian Mutiny, because had Britain lost the war, its prestige and influence in the very different post-colonial age of a rapidly globalising world would have been as seriously eclipsed as would have been the case if the UK had lost the Indian Sub-Continent in 1859. The number of Gurkhas (mainly the Rifles but others in support) participating in the conflict were few. The Gurkha impact was again entirely disproportionate to numbers, being related to one of the most important dimensions of warfare throughout the ages: destabilizing fighting capability of frontline soldiery and officers of the enemy – the morale collapsing factor. This factor is recorded below, and comprised the Gurkhas reputation as an implacable and deadly foe going before them, and certainly further enhanced by some Gurkha frontline actions in the distant South Atlantic islands.

In the Falklands, soon after the war had ended, I found myself talking to a captured Argentine major, a character whose scarred face bore testimony to battle-hardened valour. As we discussed the relative merits of our fighting men, he suddenly shook his head and looked very serious. “Let me impress on you one thing,” he said. “Our men knew well in advance the reputation of your front line regiments like the Guards and the toughness of the Paras. But do you know who frightened our men the most? The Gurkhas, those little men from Nepal.

Source: https://www.express.co.uk/expressyourself/98467/Our-greatest-Gurkha-heroes

The fear factor noted in the interview with a major of the Argentinian Army, above, was well justified, for in the Falklands War, although small in number of combatants, the Gurkha (again, largely the RGR) contribution to the British victory in retaking from the Argentinian military, the British colony [overseas dependency] in the remote South Atlantic, was vast in terms of engendering very justified fear of swift and violent death in the hearts of those facing them.

The 1994 to 2020 period — The Balkans (Bosnia, Kosovo, Macedonia: UN Peacekeeping) to Iraq and Afghanistan:

The RGR saw deployment in the NATO ‘SFOR’ (Special Forces Bosnia & Herzegovina) peacekeeping force in the Balkans in 2001 via the British Army’ UK Battle Group (UKBG). SFOR being instituted to enable Bosnia after the horrors it experienced in the Serbia – Croatia – Bosnia conflict (with Bosnia & Herzegovina’s largely Muslim population being targeted to the point of genocide through the infamous ‘ethnic cleansing’ practiced against the latter by hard-line elements of the two neighbouring Christian [Roman Catholic for Croatia, and Orthodox Christian for Serbia] states). UKNFS contacts in the Aldershot area in particular shared about RGR soldiers and officers services at that time in Bosnia showing the strength of the efficiency and effectiveness of the Gurkha forces in regard to support on shared humanity characteristics in the peacekeeping setting of Bosnia. These sources recommended online articles about the RGR operational theatre activities in Bosnia, with in particular one below, excerpts of which we are pleased to cite, in which Gurkha communication skills affability aplomb emerges in conjunction with their much better well-known frontline skills as vanguard operational level experts and warriors:

New members to the United Kingdom Battle Group (UKBG) include a battalion of Gurkhas, Nepalese warriors with a long history of service in the British Army. Their unquestionable soldier skills and engaging personality make them invaluable assets in carrying out SFOR’s mission of maintaining a safe and secure environment in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH).

Mrkonjic Grad – Outside the British Bus Station Camp, Gurkha troops mingle with local children. Only a week in BiH, the soldiers are already trying out some Bosnian phrases with the kids. Communication seems to come naturally to the Gurkhas, and soon the children are smiling.

Just across the street a few soldiers are preparing for a visit from COMSFOR, U.S. Army Lt. Gen. John Sylvester. Before the Blackhawk helicopters land with the general and his entourage, Gurkha riflemen secure the area surrounding the landing site. So practised is their field craft, none of them can be seen.

This is the dual nature of these soldiers from Nepal.

“The Gurkhas have a natural charm, but they also have excellent warrior skills,” said Lt. Col. Ian Thomas, UKBG commander.

The combination of skills makes the Gurkhas particularly well suited to the mission of maintaining a safe and secure environment in BiH, Thomas added.

“We want to earn the respect and trust of the people in our area of responsibility so they feel confident in our ability to promote the secure environment. The Gurkhas are an engaging people and can be a reassuring presence, but that presence is also a deterrent force,” he said.

The Gurkha force is nearly 500-strong in BiH. All infantrymen, they are from the 2nd Battalion, Royal Gurkha Rifles (RGR), based in southern England. Along with a company of Royal Engineers, a cavalry squadron and an artillery battery, the Gurkhas help make up the UKBG.

“We’re very looking forward to the tour,” Thomas said. “We can bring a lot to the mission.”

He added that the interaction between Gurkha and British troops within the battle group has been a “seamless coming together.” Thomas attributes much of this to the long history of trust and respect between the two.

Source (Sgt. Peter Fitzgerald: SFOR Informer): https://www.nato.int/sfor/indexinf/124/p04a/t0104a.htm

The peacekeeping dimension of the Gurkhas as a window on the unique range of interconnected expertise, characteristics and aptitudes that the Gurkhas encapsulate certainly reflects honour on the British name, through the British Army. Why, because in the peacekeeping role and still more how that role is discharged, the name ‘Gurkha’ – and therefore the names of ‘Nepali’ and ‘Nepal’ and by extension the cultures of the Gurkhas and related South Asia – has brought perhaps as no other single people have, a reputation that being a peerless effective protector of the most defenceless against the most brutal is in proportion to a global level reputation of the very same peacekeepers being the most ferocious and lethally effective, focused soldiery and officers in the world.

Kosovo:

In addition to Bosnia, Kosovo (and to a lesser extent, Macedonia) were Balkans peacekeeping operations under NATO and especially the UN, where the Gurkhas provided vanguard — including often the most dangerous types of activity such as military presence ‘making safe and securing’ key locations, as well as mine and concealed arms dumps clearance — operations under the aegis of the British Army whose given leads assigned the Gurkhas (especially foremost the RGR) these strategically most important and personally perilous, tasks. We provide below a news report below:

“We are the fighting force, but wherever we go there will be peace. It is our history.”

The words above are from an unnamed British Army Gurkha infantryman serving in the Gurkha component of the British Army in Kosovo, in regard to his very – on the basis of the record of history – accurate and perceptive appraisal of the ultimate outcomes of engagements in battles, and by extension in some instances battles within wars of geo-political major significance (such as in the British contexts of the Indian Mutiny and the Falklands).

Source (BBC: Monday June 14th 1999): http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/367951.stm

We provide the full BBC news report below, for its particulars are important to share with both the general public, and especially policy formers in Whitehall and Westminster:

Gurkhas enter Kosovo: ‘Wherever we go there will be peace’

‘Gurkhas: A force to be reckoned with’

“Better to die than be a coward” – the motto of the world famous Gurkha soldiers.

It is surely no coincidence that the British Army chose these fearsome warriors from Nepal to spearhead a multinational force for Kosovo.

About 660 men from the 1st Battalion of Royal Gurkha Rifles, together with the 1st Battalion the Parachute Regiment, form the 5 Airborne Brigade, which numbers around 2,000 men.

Their role in Operation Joint Guardian is to secure a path into the province for the heavy armour of the King’s Royal Hussars and the Irish Guards.

In the vanguard

“The Gurkhas are in the vanguard of any move into Kosovo,” a spokesman for the Ministry of Defence told BBC News Online.

“They were flown into Kosovo by Chinook and Puma helicopters on Saturday, where they established a route into Pristina by securing the main road.”

While they awaited their orders, the Gurkhas trained with the Paras at Petrovac in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.

They are equipped with modern SA80 rifles and are renowned as natural marksmen. But they still carry into battle their traditional weapon – an 18-inch long curved knife known as the kukri.

In times past, it was said that once a kukri was drawn in battle, it had to “taste blood” – if not, its owner had to cut himself before returning it to its sheath.

Now, it is used mainly for cooking, but one Gurkha in Macedonia told reporters: “When the ammunition runs out we still use them.”

“We don’t expect to use them, but we would not be Gurkhas without them,” said 25-year-old Tirtha Ghale.

Single-handed hero

In the 185 years they have served in the British Army, the Gurkhas have won 26 Victoria Crosses, more than any other single group in the army.

Havildar Lachhiman Gurung won his VC by preventing the escape of Japanese forces in Burma in 1945, literally single-handedly.

He threw back three hand-grenades thrown into his trench – the third of which blew off his right hand.

In spite of his wounds, he carried on fighting, firing and re-loading his rifle with his left hand for four hours.

Loyal fighters

The British first realised the potential of these fearsome warriors at the height of their empire-building in the last century.

After suffering heavy casualties in the invasion of Nepal, the British East India Company signed a hasty peace deal in 1815, which also allowed it to recruit from the ranks of the former enemy.

Since then, the Gurkhas have loyally fought for the British all over the world, and their British officers are taught the Gurkhali language.

More than 200,000 fought in the two world wars, with 14,000 killed in engagements in France, the Middle East, Gallipoli, Italy, Greece and South East Asia.

In the past 50 years, they have served in Hong Kong, Malaya, Borneo, Cyprus and the Falklands.

With deep defence cuts, their numbers have been reduced to 3,600 from a World War II peak of 112,000 men.

After being stationed in Malaya – as it was then known – and Hong Kong, the Gurkhas are now based at Church Crookham in the English county of Hampshire.

Only the toughest

The selection process has been described as one of the toughest in the world and is fiercely contested.

Young hopefuls have to run uphill for 40 minutes carrying a wicker basket on their back filled with rocks weighing 70lbs.

This year, 36,000 young would-be Gurkhas competed for just 230 places.

Hardly surprising then that Gurkha soldiers on their way to the Balkans relish the chance to show off their prowess.

“We are looking forward to this new challenge,” said one infantryman. Another said: “We are the fighting force, but wherever we go there will be peace. It is our history.”

Iraq:

Source: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Gurkha-Rifles/

Historic UK .Com has been recommended by retired Gurkhas who served in Iraq.

Even though, sadly, there is at the time of completing this information resource (summer 2020) minimal information provided on Gurkha contributions to the Kuwait liberation war, and subsequently later the Iraq War in which the Western Allies occupied Iraq, the Gurkhas were honourably involved in both wars: in our Band of the Brigade of Gurkhas reference is made to the Band’s presence in the Kuwait liberation engagement, and here we provide a BBC news link in regard to a medal award to a Gurkha for outstanding service in the second Iraq War: http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/vkUb8PO7TEKwp1EIS_K1AQ

Comments on the article above:

Dipak is a Gurkha serving a 22 year contract with the British Armed Forces. He was awarded this medal for his service in Iraq in 2008. Gurkhas come from Kathmandu and have served with the Britiah Army for more than a hundred years.

Maybe, Dipak is from Kathmandu but all the Gurkhas do not come from Kathmandu.

NOTE: The news item is poor in quality of accuracy to a level of cultural insensitivity — ‘Gurkhas come from Kathmandu and have served with the British Army for more than a hundred years’. As this is from the state news broadcaster, the BBC, the errors (factual, and a careless typing spelling) are particularly alarming. Disrespect was evidenced by Dipesh’ position/post in the British Army not being provided, and by no information on his particular, doubtless exceptional frontline service being detailed: the culturally incompetent point on criticism of an almost 19th Century British colonialist style tactlessness on the journalist’s ‘Gurkhas come from Kathmandu’ error, is symptomatic of such incompetence in understanding about the Gurkhas and the Gurkha – British Army history and interrelationship. Suffice it to say British Army Gurkhas served, and with honour, in the second Iraq conflict.

Afghanistan:

The two images above are kindly provided by Sgt Hiradhan Rai, who features in the centre of both photographs, taken with soldiers of the Afghan Army

The role of the British Army Gurkhas in the West’s (USA led, British supported) interventions in Afghanistan over the past two decades provide the concluding part of the history section of the UK Nepali Gurkha information resource.

That day a lone Gurkha took out 30 Taliban using every weapon within reach

To say that Gurkhas are simply soldiers from Nepal would be a massive, massive understatement. If there’s a single reason no one goes to war with Nepal, it is because of the Gurkhas’ reputation. They are elite, fearless warriors who serve in not only the Nepalese Army but also in the British and Indian armies as well, a tradition since the end of the Anglo-Nepalese War in 1816. They are known for their exceptional bravery, ability, and heroism in the face of insurmountable odds. Faithful to their traditions, one Gurkha in Afghanistan, Dipprasad Pun, singlehandedly held his post against more than 30 Taliban fighters.

It was a September evening in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province. It was 2010, and Sergeant Dipprasad Pun of the Royal Gurkha Rifles was on duty at a two-story outpost. He heard some noises and found two insurgents attempting to lay an IED in a nearby road. He realized he was surrounded. The night sky filled up with bullets and RPG fire.Taliban fighters sprang into a well-planned assault on Pun’s outpost.

Pun responded by pulling his machine gun off its tripod and handholding it as he returned fire toward the oncoming fighters. He went through every round he had available before tossing 17 grenades at the attackers. When he was out of grenades, he picked up his SA80 service rifle and started using that. He even threw a land mine at the enemy.

As Pun defended his position, one Taliban fighter climbed the side of the tower adjacent to the guard house, hopped on to the roof and rushed him. Pun turned to take the fighter out, but his weapon misfired. Pun grabbed the tripod of his machine gun and tossed it at the Taliban’s face, which knocked the enemy fighter off of the roof of the building.

Pun continued to fight off the assault until reinforcements arrived. When it was all said and done, 30 Taliban lay dead.

He was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross by Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace.

“At that time I wasn’t worried, there wasn’t any choice but to fight. The Taliban were all around the checkpoint, I was alone,” he told the crowd gathered at the ceremony. “I had so many of them around me that I thought I was definitely going to die so I thought I’d kill as many of them as I could before they killed me.”

In all, he fired off 250 machine gun rounds, 180 SA80 rounds, threw six phosphorous grenades and six normal grenades, and one Claymore mine.

Pun comes from a long line of Gurkhas. His father served in the Gurkha Rifles, as did his grandfather, who received the Victoria Cross for an action in the World War II Burma theater.