British Library Nepal collection sourced painting ‘Assemblage of Ghoorkhas’ 1820

This section includes important ‘need to know’ details about the background to the emergence of the phenomenon of Gurkha martial prowess in conjunction with the creation of Nepal and ultimately the Nepal – British special friendship through which provision for recruiting from Nepal for the British Army commenced. However, as much of the history of the Gurkha component of the British Army (from British Empire phase to modern UK) is linked to specific regiments (such as the Sirmoor Rifles Regiment) and functions, we have provided sections on these, where more detail is provided – taken together we have with the help of retired and serving Gurkhas directly, provided valuable signposting to respected sources of Gurkha history in the UK and Nepal, at the direction of our contributors; these sources include the Gurkha Museum (Winchester), Gurkha Museum Pokhara (Nepal).

Modern Nepal was born in the 1770’s under the lead of the King of Gorkha, Privithi Narayan Shah (portrait above), who for years before this period built up the martial strength of Gorkha.

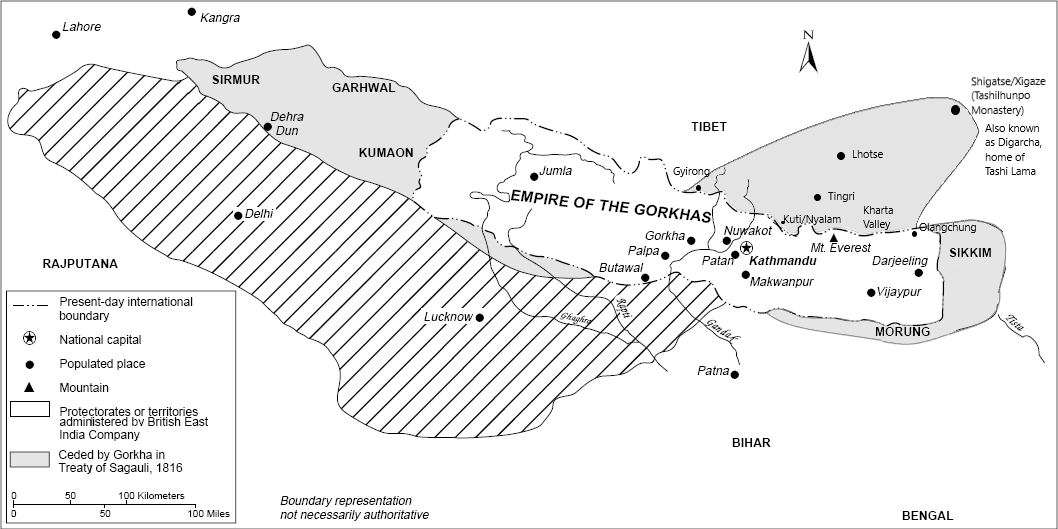

In the 1810’s Nepal was a state considerably (33%+) larger than its current 21st Century area: it’s de-facto area of outreach was much broader than this, including all of Sikkim, much [Kumaon region particularly] of modern day Uttarakhand state in modern India, and beyond, for a time past Lucknow and Delhi. As such, in the late 18th Century it had conquered an extensive territory in the Western Himalayan area (now a part of the Indian state that became an independent nation within the British Commonwealth on 15 August 1947) of what subsequently became a part of one of the states of the new [1947] country of India which became fully independent in January 1950.

Originally, the territory of Nepal in the late 18th Century was a patchwork of different independent kingdoms, with the three most important – Kathmandu/Patan/Bhaktapur – being in the Kathmandu Valley. Late 18th Century Nepal also comprised a Greater Nepal, Empire of the Gorkhas that extended into substantial parts of current southern Tibet and northern parts of the Republic of India.

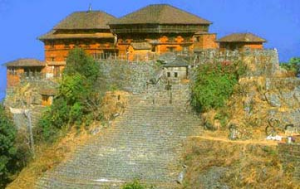

The Principality of Gorkha (image of the Gorkha Palace – Citadel above) from which the name Gurkha is derived, under its ruler the Maharaja (‘Great King’) Prithivi Narayan Shah ( 1723–1775): last King of Gorkha, first King of Nepal (also known as the Kingdom of Gorkha). With Prithivi Narayan Shah’s (portrait above) conquest of the Kathmandu Valley kingdoms the stage was set for the creation, unification and subsequent expansion of Nepal.

The name ‘Gurkha’: derived directly from the name of the town of Gorkha, the origins date to the medieval period as Gorkha itself in turn gained its name through being the location of a famous warrior saint, Guru Gorakhnath, who has a shrine dedicated to his honour in the town.

By appropriate destiny, during the period of the creation of the resources of the UK Nepali cultural & social heritage project, the martial associated town of Gorkha came to be twinned with Rushmoor in the UK, where is located Aldershot ‘Home of the British Army.’

In the 1810’s Nepal was continuing on its expansionist path (the Nepal/Gorkha Empire was at that point equal in territory to the British Isles [UK and Ireland]), and much of the southern flank of the mighty Himalaya and down in to the Mahabarat range, mid-hills and northern parts of the plains (Terai) southmost part of the country were under its sway.

At the same time, the then British Empire, under the East India Company had conquered, annexed directly or else forced client state protectorates status across the Indian Sub-Continent. A clash was inevitable between the two expansionist powers, one Western, one indigenous/South Asian. This set the scene for the Anglo – Nepali War (1st November 1814 with armistice signed on 2nd December 2015, with the formal end of the war): more on particulars of importance below and elsewhere in this information resource, concerning significant engagements.

Consequently, establishment of a new chapter in Nepal – UK relations commenced on the 4th March 2016 with the signing of the Treaty of Sugauli. The treaty was to some extent an unequal one with aspects of Nepal’s sovereignty being impinged on (a British Empire residency for example was imposed, situated in Kathmandu: image below): however, the Nepal – Britain Treaty of 1923 resolved this, establishing beyond all doubt Nepal’s status as an independent state, further reinforced with the treaty being recorded two years later (1925) at the League of Nations.

Kathmandu 1850: watercolour painting of the British Residency – source: British Library Nepal archives

There has for the interest and reference of 21st Century British audiences learning for the first time about this crucial formative stage of the Nepali-Gurkha, Britain/British Army relationship that was to subsequently develop after the Treaty of Sugauli, been a topic of great importance regarding this very important time.

Elements, that doubtless have lingering attachments to the British overseas conquests [invasions] colonial era, regarding the hypothetical notion put out by those not comfortable with the might of the British colonialist empire being held in check, and by non-British/non-Western/non-Christian, Asian warriors, have put out the following notion:

That if the British Empire military forces had wanted to at the time, they could have pushed on and conquered and annexed or otherwise subjugated all of Nepal: they were so powerful, etc. etc. … the territory was poor in natural resources, etc. .. not therefore worth the effort to pursue further military conquest etc. etc.

The realities were that the war involved British Empire forces [East India Company] invading on a major scale, a sovereign state, not by chance, but for reasons of strategic territorial conquest interest: Nepal was the independent state standing in the way of long desired penetration of British Empire power directly from its Sub-Continent dominions to Tibet and China (more on this towards the end of this topic overview).

The ferocity of the defence ultimately led to an armistice in which almost all of the core Kingdom of Nepal territory remained independent/not annexed. Whilst there were some restrictions on Nepal’s independence, de-facto independent the kingdom remained and was never subject to nominal independent vassal client states/protectorates as occurred across many parts of the Indian subcontinent, where such territories could be formally absorbed into the British Raj on minor pretexts when extreme conditions imposed on rulers and populations of such territories, caused resistance to the foreign occupier. Nepal Never suffered this fate.

World history geo-political significance in regard to Nepal retention of independence:

In fact Nepal’s continued independence [an unlooked for irony of the terms of the Treaty of Sugauli] effectively put an end to British Government [Whitehall and 10 Downing Street] dreams — mobilised by British Empire business houses and supported by many Christian missionaries of that colonial ear (the European colonial Powers formula of ‘bullets & Bibles’ used for centuries in overseas expansions) – of extending its power into China via Tibet, to a level attained in the Indian Sub-Continent.

Nepal, a continuing independent Nepal, controlling all of the central sector of the Himalaya trade routes and strategic passes, the bond of special friendship at the heart of which were and remain Nepal’s Gurkhas, meant it was effectively impossible to use the type of force and diktat British and other European colonial powers used elsewhere across the globe, to effect this extension of power and conquest from South Asia to East Asia.

Seaward penetration of the mid to late 19th Century ailing Qing [Manchu] Chinese Empire, was never going to be a substitute for substantial invasion/influence landward from the South West: as such British colonial influence (including of course the infamous use of Opium addiction to gain and extent influence in China) had via the coastal areas and later the greatest rivers of the Chinese Empire, to compete with other European powers and of course Imperial Japan – challenges and competition that they would never have had to face from landward/South Western penetration.

What is little-known generally in the UK and overlooked by those recording Nepal – UK history in various domains, is a key fact and a related affirmation of the unique role an independent (or rather, a not conquered and turned into a colony by the British Empire) Nepal played in this crucial part of world history regarding tipping points in the struggle of invaded lands and peoples with foreign/Western colonial powers.

At the time of the Anglo-Nepal mid 1810’s war, for some twenty five year’s Nepal had been prior to that time been recognised as a Qing Empire ‘tributary’ state (similarly Ladakh to the North North-West): the Sino – Nepalese War (also known as the Sino – Gorkha War) of 1788 – 1792 that commenced with Nepal invasion of Tibet, with eventual treaty favourable to the Qing Empire that resulted in this status has parallels with that of the Anglo-Nepal War in terms of outcomes.

Nepal didn’t win this war, but Nepal didn’t lose its de-facto independence either, becoming only a very nominal ‘tributary’ state of the Qing Empire at the acme of its power, and with the very new Kingdom of Nepal [Gorkha] still in a state of consolidation within its core territory. As such if the Anglo-Nepal War had resulted less in stalemate, and instead in unambiguous British/East India Company victory, Britain would have found itself in the position of seizing a Chinese Empire tributary state, with very extensive implications for both Britain and China.

Decades on, in the years 1855 – 1856 Nepal invaded Tibet, and was nominally the winner of the war: Nepal’s military however was however more effective than the army of the defending Tibetans. An armistice and then a formal end of the war was agreed and signed favourable in minor but symbolically important terms to Nepal, in Nepal’s capital through the Treaty of Thapathali in March 1856. A nominal annual tribute was to be paid by Tibet to Nepal, and more importantly a formal Nepal presence was imposed in Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, this taking the shape in particular through a Nepal trading post. From that point Nepal’s nominal tributary of the Qing Empire status was ended, and to – albeit a very limited degree – Tibet became technically-speaking a nominal tributary state of Nepal. The infamous ‘Opium Wars’ with China, and other destabilising impacts of European Colonial Powers (Britain to Germany) and their interest in turning the Chinese Empire into ‘zones of influence,’ and most of all for Imperial China the destabilising impacts of the fourteen years long (1850 – 1864) ‘Taiping Rebellion’ cumulatively saw the end of the Chinese Empire. Its demise a matter of ‘if’ but ‘when’ in the early yeas of the 20th Century – a situation that also saw the then Japanese Empire take a comparable predatory colonial acquisitions approach.

From the above, the folly of those de-facto covert or unintentional proponents of 19th Century European Powers colonialist and related Western supremacist world views that argue that in effect ‘Britain was generous to Nepal, and only didn’t push on to conquer it, because it didn’t have enough wealth or natural assets to make this worthwhile’ can be seen for what they are: self-delusional at best, disingenuous at worst.

More importantly, it cannot be doubted that through Gurkha martial prowess first and foremost, because Nepal’s independence was maintained post-Treaty of Sugauli, an independent Nepal (still ready and able long after Sugauli to invade much larger states to the north of its borders) ended forever the opportunity for landward penetration and progressively implemented seizure of China from the West. This a matter of the greatest geo-political significance in world history.

It is appropriate at this point of this, background and history section of our information resource to raise the matter of certain elements who not stating, but doubtless confused by and uncomfortable about Nepal’s Gurkhas world renowned military prowess and its unique contribution to by its very special role within British military and British Army history to Britain’s history itself to address the question ‘are the Gurkhas mercenaries?’

This question is one that has frequently been raised in regard to the association and connection between the Nepali Gurkhas and the British Army from the commencement of the special relationship between Nepal and the British state in terms of the latter’s engagement of Nepalis – the Gurkhas – within the British Army.

For those with selective to non-existent knowledge of the actual history, this question has from time to time arisen; it has doubtless also arisen in the selective/non-objective thinking of those on the British side who have issues with a key component of the British Army having such an illustrious reputation and key role in the history of the UK at geo-political and British Army due to its martial prowess and crucial role in critically important military engagements in key campaigns of fundamental importance to the military history of Britain. Some – those with a competent knowledge of the actual facts and record of history — could consider therefore the ‘mercenary’ imputation, an unjustifiable slur, and one made potentially from out of date Western colonialist supremacist [and by extension neo-racial imperialist] unstated perspectives. Whatever may be the case in regard to this question, it is valuable here to provide clarifying definitions; definitions of what a mercenary is in objective terms. On this, two essential need-to-know considerations are, and remain:

As such this Gurkha component of the information resource presents a de-facto holistic British Empire to modern inclusive 21st Century British Army (that celebrates diversity and especially the exceptional role of the Nepali Gurkhas in its history and current forces) voice – from guidance and multiple sources support – of the UK Nepali Gurkhas on their contribution to our nation: a contribution of the most exceptional, defence and geo-politically important kinds for modern Britain and All British citizens.

The next, and a major section of the Gurkha component of the information resource covers the main Brigade of Gurkhas regiments characteristics and histories.