In almost all if not all UK Nepali families homes will be found sacred Nepali Hindu or Nepali Buddhist (including Sherpa-Tibetan) or images, framed or even simple colour photocopy formatted, but All venerated – foci of connection with Nepal’s spiritual and religious cultures in the homeland, and of devotion for prayer and on special family, personal or cultural festival occasions (such as Tihar/Divali). Beyond the formal spiritual/sacred visual arts (as with architecture, sculpture, metalwork) the visual and fine arts of Nepal are vast,

In terms of visual arts, the UK is also home to two very different in terms of styles and artistic topics for their brilliant creativity, yet united by the underlying theme that painting and other art forms are ultimately spiritual activity, internationally renowned painters, Govinda Sah ‘Azad,’ and Subesh Thebe, who have provided exclusive interviews (below) for the information resource.

Following on from Govinda and Subash’s interviews, we provide interview responses from Bournemouth-based artist, former Bournemouth & Poole College arts student, Tom Pouncy: his participation in a UKNFS enabled major transcultural arts learning project at the college referred to, led him to making an artist’s learning pilgrimage to Kathmandu and Nepal.

UK Nepali artist Govinda Sah ‘Azad’ interview:

Govinda Sah ‘Azad’ was born in 1974, in Rajbiraj, Nepal. From an early age he was interested in drawing and sculpture. He left Nepal to live in India and from 1991-94, worked as a sign board and wall painter in Delhi. In 1995, he returned to Kathmandu and joined the Fine Art College to realise his dream to become a painter. It was at this point that the Professor and Campus Chief of the Fine Art College and prominent artist Govinda Dongol dubbed Govinda Sah as “Lion Heart”.

From March-June 2000, Govinda began a nation-wide cycle tour to spread the awareness of peace through art under title The 21st Century is the Century of Art and Peace. During the three-month tour, he held several art shows, workshops, and gave lectures in schools and to community groups.

Govinda obtained a MA in Fine Art from Wimbledon College of Art in 2008. Some of his exhibitions have been sponsored and organised by the British Council in Nepal and Egypt’s Ambassador to Nepal. Govinda Sah’s works can be found in private collections worldwide.

Source: http://www.octobergallery.co.uk/artists/sah/

Question 1. If you were to explain to a non-Nepali, non-South Asian, Western British person what is the unique defining essence of Nepali art, what would you say it is?

Response: It is about spirituality in life, nature and human existence. At a human, artist level it is reverence for the spiritual through ancient spiritual values and philosophies that link Heaven, Man, Nature, seen in Nepali Hinduism and Nepali Buddhism. This reverence is seen through the devotion as well as subjects depicted by Nepali artists whether in sculpture and woodwork in our temples or in Thanka art. There is a mystic heart to Nepali religious & spiritual art, esoteric and often shamanic in character.

This is about energies, spiritual vibrations ultimately, the dynamics at the heart of profound spiritual truths, which in the Nepali and South Asian arts case are intimately linked to the attributes and the essences and powers of the gods and goddesses.

The ‘Glorious Wheel of Creation’ (in Sanskrit: ‘Shristi-Chakra’) from Govinda’s show in New Delhi in 2012 exemplifies this so well. Derived from the Mandala concept, sacred geometry is powerful in the piece, with the depiction of a Tantric diagram, known as a ‘Yantra.’ This latter the divine source of emanation from the centre, beyond which are amorphous clouds in which energies are revealed and take form.

I am pleased to provide this January 2013 quote about this very subject of East – West interconnection in my work and vision, from an interview with Robert Beer:

‘Govinda recognises that his artistic roots first germinated from the unique fusion of Hindu and Buddhist Tantric traditions that are found in Nepal. But his …blossoming personal style of painting increasingly encompasses the visionary realms of intergalactic fields …’

Question 2. What do you feel is the defining characteristic of British art compared to Nepali art, and are there any similarities with the latter?

Response: I would say it is experimentality in technique; originality in composition and sometimes subject. On approach to art, in contemporary terms there are still major East – West differences of approach. I reflect on this very topic in an interview with Gerald Houghton when discussing my response to British art critics asking me questions, specific questions about my artworks and what through them are the questions I am raising and seek to resolve through art:

There is also this, that Nepal is a totally different cultural matrix, a way of being based on different premises. We do things without always asking why; the answer’s already understood, so, in Nepal, we don’t need the question. Here [the West / UK] everyone questions everything, and you must be able to explain things precisely too.

But I must stress that there are major differences on such an approach between older, 19th Century in particular renowned British artists such as in particular Turner and Constable, and approaches to art and art criticism in early 21st Century Britain. I believe these two artistic convention breakers, pioneers who went on before their ends to become household names, have in their inspirations teachings which I connected with at a deep level when I was first brought in to contact with them through seeing and contemplating on their work, at technical technique level and still more the essence each conveyed. I have seen myself as, particularly Turner, spiritually speaking as their disciples. My fascination with the mysteries of light as a subject linked to the most ancient and profound of spiritual concepts on Life, the cosmos, the microcosm to macrocosm interconnection and synthesis are seen in many of the most famous later works of the great Turner, and in my main subject pieces.

Question 3. In what way do your major works have any direct inspiration from Nepali traditional art and what message do they convey to viewers in the West?

Response: Neither the West nor the East is superior to the other where creative inspiration takes place in the soul of the artist. But yes, definitely each has something unique and my major works of art call on my inspiration from Nepali spiritual cultures. My most iconic and important works, my cloud and galactic and nebula pieces certainly at subliminal level take some of their power from those cultures. I have on the spiritual dynamic at work in these explained before and repeat here:

‘ … my work becomes an abstract meditation on the wonders of the whole universe and of the spectacular natural phenomenon contained therein, irrespective of scale.‘

Thank you for this opportunity through the UK Nepali heritage project, to be able to contribute to this exciting topic of that part of the arts heritage of British based Nepali artists such as myself and my good friend Subash. It has given me valuable opportunity for reflection, and the part of a given ethnic minority’s cultural heritage that is a synthesis of that of land of birth and land of settlement is such an important one. Here we see, and particularly through art, how two cultural heritage can blend to create something new and of a much broader relevance! Thank you.

We are very honoured to provide below some examples of Govinda’s ground-breaking art:

UK Nepali artist Subash Thebe interview:

Subash Thebe:

Nepalese artist. Born and raised in a small town, Dharan in eastern Nepal, Subash Thebe graduated from Middlesex University London in 2011 in BA Fine Art. Currently, he is the recipient of Vice Chancellor’s International Scholarship and doing his Masters at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, University of the Arts London (UAL). He explores the contemporary socio-political issues and its relation with media and technology. Subash lives and works in London. Source: http://www.subashthebe.com/BIO/

Interview questions context information:

“[ARTISTS] HAVE STIRRED OUR GREY MATTER AND QUESTIONED OUR CONSCIENCE AND HUMANITY. I GUESS THAT IS QUITE A BIG THING TO ACHIEVE

‘It has often been debated whether art has a moral obligation to make a political stand. Perhaps the very act of making art is a political act. Though it will never be possible to pin down any rules and expectations on artists, perhaps as human beings we are morally obliged, in the least, to inform ourselves about power.

Subash Thebe writes in his artist’s statement, “Maybe it was because of the losses we endured, I never even had the slightest thought of pursuing the British Gurkha military tradition of my community. Unconsciously, maybe I was choosing everything opposed to war and violence like art and music.”

Source: http://mydreamsmag.com/article/subash-thebe/

Question 1. What are the main inspirations you take from Nepal’s visual art heritage, inspiring your own forms of art?

Response: This project on the cultural and social heritage of our Nepali community in Britain, is a badly needed one, and the opportunity to contribute from an arts and artist perspective a great pleasure. Artists, or most artists, are by nature contemplative and reflective. The subject of what synthesis there is between two very different artistic cultural traditions and if there is a building of a new, hybrid form in the work of artists like myself and Govinda, is exciting because it speaks of what unites not what divides, it speaks of our shared humanity.

In answer to this question, the forms of inspiration, I have always been inspired by the practical ethics teaching concealed within Nepali religions legends and tales; doing the right thing in the face of moral dilemmas, Nepali Hinduism and Nepali Buddhism teach this, and these legends are all about us in the sacred architecture of stone and woodwork in our temples and shrines. It can’t be doubted that this has inspired both artists and social activists, up to and into our own times.

Question 2. Do you believe there is a synthesis at any points between Nepali contemporary ethics & social comment art and the British/Western equivalent?

My triptych, The Higher Powers Command: Paint Upper Right Corner Red! Is an example of my sardonic observation on art and capitalism, and looks to the work of the German artist Sigmar Polke, and involves use of the process work of the British (London) painter Jason Martin, whose monochromatic work has a power to project its message so well and in fact constitutes a blend between painting and architecture. This echoes some aspects of ancient Nepali art well. From Polke I have come to realise the special part of an artist’s calling to be self-reflective, to pass beyond utilising technique to look at the bigger picture of what I wish to accomplish through my artwork.

This I feel connects directly with the work of ancient to contemporary artists and artisans, especially the latter, creating works on sacred, spiritual, religious subjects. The act of creativity is a type of meditative, contemplative act capable of giving whether in act of creating, or through interaction as a viewer (or listener, for music and theatre have this great power too) profound revelation or understanding of truly life transforming kinds.

Question 3. Your work is particularly inspired by ethical impetuses and how these apply in the field of counteracting acts of inhumanity and injustice; please tell us more about this?

Response: Yes I do believe there is no alternative to speaking out and calling out where unethical and inhuman conduct is concern, and that you can’t compromise with this as some do in terms of right and wrong being equal, a matter of opinion. Art gives a very special platform for speaking up and out. In my article ‘Art versus Thought Control’ (September 2014) I particularly talked about why this speaking out matters, with the topic covered in my exhibition ‘Metadata’ which is about mainstream media being revealed to manipulate current affairs and history in ways that are favourable to a very small wealthy elite.

Art such as painting, street art, and certainly theatre and the work of some of the playwrights and documentary film producers powerfully take up issues of burning injustice, and place back to the viewer the challenge of what they can do that is within their scope to give censure towards those involved in a given inhumanity or injustice, or complicit in covering it up or allowing it to continue unchallenged. In this sense I see my work as having strong ethical & moral purposes, a type of imperative that I think is something that deep down we all feel when confronted with things which are dark, and unacceptable.

Below we provide two examples of ‘Mothership’ of Subash’ exceptional artwork:

You can also read more about Subash at https://londonsartistquarter.org/artist-hub/users/subashthebe/profile

Tom Pouncy – a young British artist’s perspectives on and respect for Nepali arts:

We are delighted to provide Tom Pouncy’s insights on Nepali arts related culture. He has provided a video interview (interview link: TBA), the text interview (25/02/2020) linked to the latter, below, and also an exceptional set of images from his travels and time in Nepal where subjects have been arts, artisanship, and broader culture related (this gallery can be accessed through this link TBA, and found on the information resource website Galleries section.

The significance of Tom’s information is that it encapsulates the core transcultural learning and information purpose of the information resource project, as it witnesses a non-Nepali, British person embracing the learning and engaging experience that Nepali arts and culture offer to UK non-Nepali people, to the extent of through active participation in an earlier transcultural learning & arts project of the UKNFS – the ‘Nepal International Arts Programme’ (https://creativenepal.co.uk/).

Tom has contributed an invaluable set of Kathmandu arts and culture, with special emphasis on spiritual and religious culture photographs taken by him during his visit to Nepal, with the images provided specifically as a dedicated contribution to the UKNFS facilitated, HLF funded UK Nepali culture & social heritage information resource. Three example images are provided below, and the full set of very educational photographs taken by Mr Pouncy are to be found in a dedicated gallery in the Exhibition & Galleries (Link: TBA) section of this information resource.

Nepal Cultural Heritage Project interview with British artist Tom Pouncy

Questions:

- Could you provide, based on your experience of the BPC Nepali Arts project and subsequently visiting Nepal, your reflections on the relationship between the Arts (sculpture, architecture, paintings, music, costume) and spirituality and religions?

- In your experience, could you share your observations and reflections on points of similarity and of difference between UK/Western and Nepali arts-creativity? This could include Western adaptation of some elements of Nepali art, etc.

Introduction

Hi, my Name is Thomas Pouncy, I am an Ambassador/ Associate for the UKNFS. Undergraduate at the Arts University Bournemouth (AUB – NOT Bournemouth University), studying BA Hons Creative Management.

I was Introduced to the UKNFS in 2015, through the Nepal International Arts Project (NIAP), at the Bournemouth and Poole College (BPC), during my time studying Illustration and Visual Arts. The project set a sail of interest towards Nepali Arts and Culture, inspiring me to participate and produce geographically specific arts ideas that are based upon Nepalese Arts, Culture and Heritage. Project Leader and UKNFS Organisation Leader Alan Mercel-Sanca then assisted me in travelling to Nepal in November 2016. In order to educate myself further on the Arts and Culture sector, I had traveled to Kathmandu and had been affiliated with Saroj Mahato, founder of the Bikalpa Arts Centre (BAC) and Advisor for the NIAP. BAC is an outstanding facility for local artists and a café, in Lalitpur. It is a contemporary art Centre and platform for Nepali artists to voice their work and/ or collaborate. Additional to the Networking opportunity, I took the real advantage of exploring Nepali local etiquette. I studied, I produced Art/Photos and I spoke with many. I had been left with an integral knowledge of the Arts and Culture in Nepal.

Question 1: Could you provide, based on your experience of the BPC Nepali Arts project and subsequently visiting Nepal, your reflections on the relationship between the Arts (sculpture, architecture, paintings, music, costume) and spirituality and religions?

Initially, during my participation of the BPC NIAP, I uncovered Nepal as a home of religion. Although, the relationship between spirituality and Arts in Nepal were instantly recognizable.

The study of art was the vehicle that lead me to understand the importance of the union in their communities. How the balance between religion and artistic symbolism has affected culture in Nepal. Not only for its communities but also in tourism and representation. The Arts in Nepal are of respected heritage and are encouraged. Through traditional forms of pottery in the tradition of Bhaktapur, fabric printing, religious symbols; to varieties of craftsmanship and ways to earn money.

The Arts in Nepal are not always presented like that of western culture. Anyone is able to become an artist, however respected traditions such as the Mandala, take years of skill and patient practice and are popular Hindu and Buddhist Religious Symbols.

I had the opportunity to meet an old-Master Buddhist monk, who elaborated the meanings of different Mandala Variations. For example, the Tibetan Buddhist Thangka- Samsara Mandala, alternatively known as the “wheel of life”, took my interest. It features Shiva, a Deity of death and lord of time, holding a shield of life and death. In the centre you will see the three poisons:

- Desire, seen as the Cockerel.

- Hatred and jealousy, seen as the Snake.

- Ignorance, seen as the Boar.

Around the centre is Bardo. Which represents the path of ascent and descent in death, before rebirth. Then there is the Six worlds of Samsara, which feature in the highest order:

- Gods.

- Titans of Samsara.

- Humans.

- Animals.

- Hungry spirits and the beginning of Hell, in the Buddhist religion.

- The Damned “Hell”.

You may often also see the eight symbols of Buddhism in Mandalas. Like the Kalachakra Tantra Mandala, it is another Tibetan Buddhist practice and considered an advanced Vajrayana tradition, by the Dalai Lama. Similarly, the well-known Tibetan Sand Mandala being destroyed and released by river back into nature, is a physical artistic symbol which entails that changes are an inevitable foundation of nature.

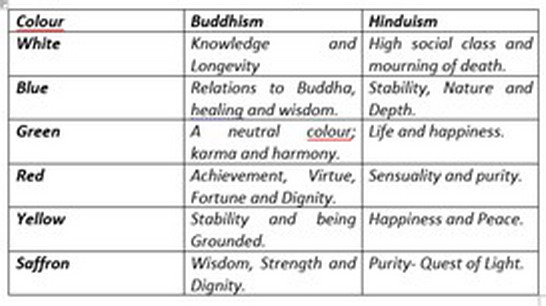

These examples could show how Artistic symbolism can be found in Nepal. The use of art in culture has provided creative stability, visual understanding and colour to Nepal. As the use of Arts and symbolism continue to unite the country, using colour as a personal expression and compassion. This could additionally be found in the famous Tibetan Buddhist prayer flags and ceremonial fashions of wearing specific colours, in death, wedding or birth. Despite the general perception on colour, religion is a unique way to express your present identity.

Colour Representations in Buddhism and Hinduism may include:

Communal understanding and respect for arts in religion have allowed the people of Nepal to express themselves in a spiritual mechanism. There are over One Million Citizens living in Kathmandu, mixed religions of Hinduism, Buddhism and Syncretism. Harmonious understanding and Visual communications are a basis of culture in Nepal. A celebration of common relations.

These were a few examples of which I saw in Kathmandu, although, this is not limited to the entire country. There are many geographic and demographic foundations in Nepal, the Arts and Culture are diverse between music and architectural structuring. Including the Himalayan and Tibetan folk music culture. Craftsmanship is spread through music and hand-crafted manufacture of instruments, like the Sarangi.

Question2: In your experience, could you share your observations and reflections on points of similarity and of difference between UK/Western and Nepali arts-creativity? This could include Western adaptation of some elements of Nepali art, etc.

With Arts and Culture in mind, structural sculpting and architecture differ greatly around Nepal. The Newari, historic creators of Nepal Heritage and civilization, often carved into the buildings; often showing Deities and Demigods of Hinduism and Buddhism. Many artworks have been classed as sacred pieces of work. You could find examples of Newari artwork throughout Nepal. Here I saw an eccentric piece, at Pashupatinath Hindu Temple. You can see the detailed art in the woodwork.

Newari craftsmanship became a recognizable influence in Tibet as I believe it supported the style of art we see related to Hindu and Buddhist art pieces, to an exquisite detail of skill and quality. In the United Kingdom, we could categorize this level of expertise as a form of ‘Fine Art’. Suggestively, this could be similar to Catholic and Christian related art works that we see in Cathedrals and churches. The artistic stylings are different but components in religious heritage could be similar, in context, to our own Religious Heritage Artworks in the United Kingdom, like Gothic Nouveau, Baroque and Renaissance – Architecture, sculptures and paintings.

Similar to the nature of wearing Shiva Eyes or wearing a mantra like in Nepal, Christians in the UK consider jewellery and accessories, like Rosary Beads or a Crucifix, to be religious symbols. Or Christians looking for blessings from a Priest, where as a Hindu may seek blessing from a Sadhu. To which I had received at Pashupatinath Temple.

And it doesn’t stop there; like the colour symbolism in Buddhism and Hinduism, Christian citizens may use fashion to cover their bodies as an expression of purity, distantly resembling a pattern in Spiritual and Religious Symbolism. The United Kingdom has been represented as a Catholic Country; our religious arts have additionally affected our global image. However, whilst the citizens of Nepal have a widespread global image with Mandalas and Statues of Buddha and others hitting mainstream industry’s; their religious attitudes and cultures are one of the most significant features to highlight.

Hinduism and Buddhism host a peaceful nature, with knowledge at your fingertips through modern technology, the Arts and Culture of Nepal has been adapted by Western countries in ways that may support the statement of “Nepal being an amazing place”. Religious symbolism is being used further than the statues and mandalas, through paintings and artworks. The symbolism used in Buddhist and/ or Hindu art is reflected in many textiles and practices.

In UK culture, our attitude towards life is based around our careers and money. It can often get slightly gloomy. The uplifting encouragement of colours, arts and peaceful culture in Nepal are a positive influence to Western society. Through Fabrics, Tapestries, Print wood block, colour use, mandalas, cultural adaptations of meditation and yoga. Many people in the Western hemisphere have found useful adoptions of Nepalese Arts and Culture as an influence in their life. Large productions of traditional Nepalese ornaments, like a singing bowl or seven metal bowl, have helped internationalize and grow Nepali heritage.

Nepal quickly affected me. It opened my World into many more thoughts and deepened my curiosity of life, it influenced my art instantly. The detail and skill of every single painting, sculpture, carving was incredible. It blew my mind; how different the two countries are. Human nature and habitual belief could be represented as an image. In heritage, in Arts and style, in nature. Nepal has a significantly colourful and Art based relationship with its heritage and Religious culture. And colours are known to directly affect your mood!

Thomas Pouncy